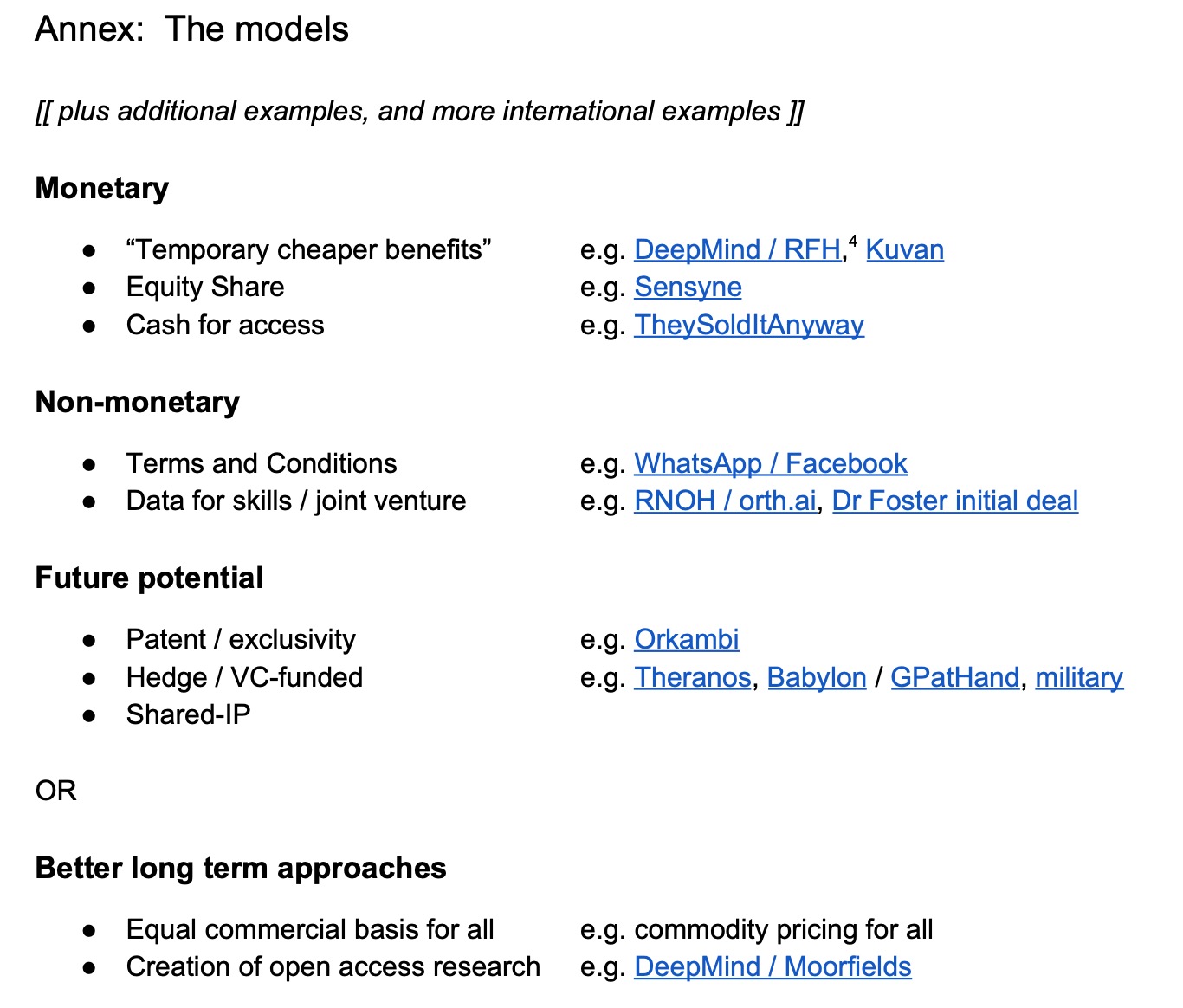

The reasoning in our short note on business models for data from 2019 holds up pretty well. Policy was a mess then and it’s a mess now as nothing substantial has changed. The re-announcement of existing work provides an opportunity to look at what happened to the examples we cited in 2019. Then it was speculation, but it played out in ways that were predictable in 2019:

What failed:

Deepmind/RFH is a mostly-forgotten debacle buried in the vaults of denial at Google Health (which no longer exists either).

Kuvan came off patent and became widely available as a commodity priced generic so it became available to everyone who needs it.

Sensyne went bust, and the NHS equity stakes got wiped out – “diluted to oblivion” as Lord Drayson put it (after he left) still insisting (Q24) his model worked (the company went bust).

TheySoldItAnyway.com – cash for access continues.

Whatsapp/Facebook – continue as AI enshittification continues to play out.

Orth.AI has rebooted as “nAItive” with the son of a Oxford Professor still in charge, denying any wrongdoing/nepotism and not explaining who didn’t know what when about the deals which resulted in the company having a copy of hospital records it tried to train models on.

Dr Foster ended their deal with Imperial and went their own way having been eaten by Telstra.

Orkambi is now permanently available in in the UK (not in poorer countries) but remains very expensive until it can be bought generically (legally here, at least).

The Theranos founders are in jail.

Babylon and GP at Hand ditched the NHS as it ran low on money, then ran out of money and collapsed.

The harms of the consolidation of supply chains became evident during covid.

What worked:

In 2019 we said:

- “Rather than focusing on speculative business models, OLS should be attempting to deliver commodity pricing for all innovations, as fast as possible.”

- “The primary measure of success should be net cost to the entire NHS and Social Care, rather than to any individual budgetary silo.”

- “All uses of data controlled by NHS bodies should be made available to the patients involved, via NHS.UK”

Successes listed have come from rapid competition to allow a diverse and commoditized supply chain. Where monopoly or profiteering were supported, temporary success was temporary and then they failed.

In the US, “Cost Plus Drugs” is the radical pharmacy undermining US problems of price gouging, but that generic-replica approach can be applied to algorithms and diagnosis tools using AI which may become available worldwide. When companies think they can make profits off a published algorithm, their profit is a negative elsewhere

The interesting case of the Deepmind/Moorfields project – 5 years on

The Deepmind/Moorfields project is the most interesting case study as it went both ways. DeepMind published their discoveries openly and freely in Nature, to wide acclaim and understanding, a model repeated in other projects that got recognition.The publication of that research means that it was available for anyone else to copy and build upon at will – the substantive knowledge was public and free for all.

Today, if you walk into an opticians, they’ll have new and better machines that can have incorporated that research to do more and tell if your sight is at risk and help you take early preventative steps, or emergency measures, to avoid going blind. There are people walking around today who would be blind without those innovations published freely and openly by DeepMind/Moorfields. This is an unalloyed good for which the benefits can be calculated (but as far as we are aware, this hasn’t been done).

However, to someone sitting in an office in Moorfields, they are disappointed that none of that benefit to people’s sight is attributed to Moorfields. Moorfields themselves have spent the intervening years trying to figure out how to charge exactly the right amount of money across different NHS balance sheets to satisfy DHSC guidance, and those other trusts have been careful to make sure they didn’t get charged too much, so nothing happened. People can see, but Moorfields (and Wes Streeting’s reannounced approach) want some cast to drop into a Moofields bucket every single time. Moorfields spent the time since 2018 arguing with others about how much that should be, and got precisely nowhere. How much is it worth to save your sight? Are you willing to pay that much to save someone else’s sight? Moorfields can’t agree with anyone else what those two numbers should be. The benefits to the public purse are massive, but Moorfields entirely disregard that and look only at their own accounting. The good thing is that the research was open and so no one had to pay Moorfields anything and people’s sight got saved anyway. That’s how progress should work.

The DeepMind/Moorfields project is how benefits can be demonstrated and realised, and simultaneously demonstrates why all too often they aren’t.

“Pharma Bro” 5 years on

We illustrated page 1 of our 2019 piece with the classic picture of the “Pharma Bro” who made money hiking the costs of non-generic drugs simply because he could, and then went to jail for fraud. He’s now out of jail but remains banned for life from the pharmaceutical industry (at the time of writing – he may get that restriction quashed by Trump2).

Seeing that as a constraint, he pays for AI compute time to build models of novel pharmaceuticals and releases them onto the internet for free, undermining the industry he’s banned from. If the drugs work in testing, there is prior art to undermine a profiteering patent (in his theory, in practice, who knows?)…

The same approach can be taken to get commodity pricing for algorithms. If one bit of the NHS thinks it will make money from selling what is publicly available, there should be a small prize fund to reward bored PhD students who replicate it and give it for free to all the other NHS Trusts and healthcare organisations for them to test internally and use internally. The US model is how to scale that.

In the NHS, any money one organisation makes from selling innovations will largely come from the budgets of other NHS entities and so the “innovation” income lauded by Streeting is simply taking money out of other NHS budgets. It is not quite a zero sum game, it is worse than that as overheads (tax, transactions, admin, interest, VC payback, etc) will eat some at every stage. If you get £1 profit into an NHS budget, it’s probably £3 or more cost to later NHS budgets.

2019+5: Still “Between Goat Rodeo and Black Elephant”

Five years after our original draft, there are a few new examples, but the thesis from then held. While the examples of barriers and profiteering lauded in 2019 have largely collapsed, as those who profited from the collapse remain in denial (Q24, theranos). Those who offered commodity pricing all survive.

The Office of Life Sciences and Department of Health in England thinking on business models continues to bounce “Between Goat Rodeo and Black Elephant” based on the interests of the day, while DeepMind/Moorfields deserve recognition (and calculation) of how many people’s sight was saved as a result. Just because it doesn’t appear on an NHS balance sheet doesn’t mean it wasn’t a benefit.

Done responsibly, correctly, without profiteering, diagnostic algorithms may be one day seen like vaccines, which are currently the only “prevention” that is so effective many forget what has been successfully prevented by innovation.

[November 2025] Some more “Intellectual Property Guidance” has been published, which changes and says nothing meaningful. The tension remains unaddressed between growing the life sciences economy which is DSIT’s goal, but minimising cost to the NHS which is DH’s goal – and there’s currently a mutually unsatisfying drunkards walk which is doing neither of those things while complaining about the failures of both. Instead, life sciences complains that prevention doesn’t give enough ongoing revenue, and the NHS NHS complains the savings don’t appear on their budgets – neither of which make any sense from the respective of the UK public interest as a whole. Maybe someone recognised failed leadership.

Enc:

==

In addition to our annual-ish newsletter, you can also join our free substack to get emailed whenever we post some news or commentary.