Every flow of health data should be consensual, safe, and transparent. The Wellcome Trust found that up to 39% of people would have concerns about the use of their hospital data (page 92). Those concerns are well founded, and the safeguards currently insufficient.

NHS Digital says that the “pseudonymised Hospital Episode Statistics” of each man, woman and child in the country are not “personal confidential information” and so your opt outs don’t apply. But the Hospital Episode Statistics are not “statistics” in any normal sense. They are raw data; the medical history of every hospital patient in England, linked by an individual identifier (the pseudonym), over the last 28 years. This article is an explanation of what that means, and why it is important.

To understand the risk that NHS Digital’s decision puts you in, it is necessary to see how your medical records are collected, and what can be done with them when they have been collated.

A proper analogy is not to your credit card number, which can easily be fixed by your bank if compromised; but the publication of your entire transaction history. Your entire medical history cannot be anonymised, is deeply private, and is identifiable.

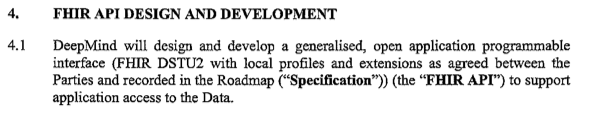

How do your treatments get processed?

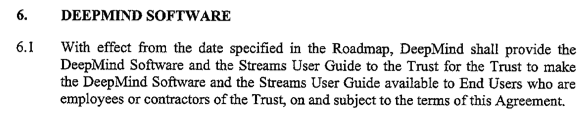

Each hospital event creates a record in a database. Some large treatments create a single record (e.g. hip replacement); some smaller routine events create multiple records (e.g. test results).

The individual event may be recorded using a code, but the description of what each code means is readable online. As Google DeepMind asserted, this data is sufficient to build a hospital records system (we argued that they shouldn’t have; we agreed it was possible).

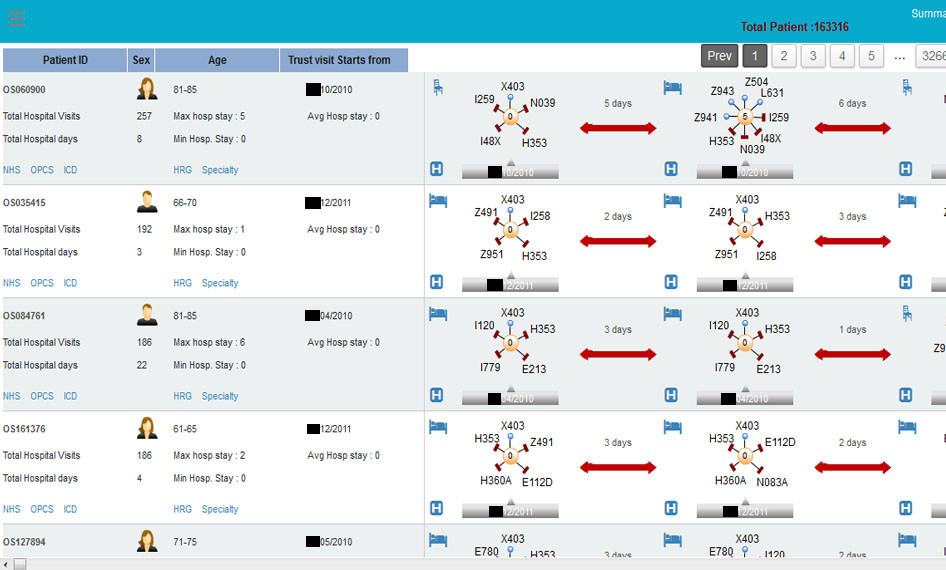

As for how millions of those single events get put together, here’s a screenshot of the commercial product “HALO Patient Analyser”, sold by a company called OmegaSolver, which uses the linking identifier (the pseudonym) to do just that:

The identifier links your records, and that’s the problem.

While a stolen credit card number might sell online for $1, a stolen medical history goes for more like $100.

The loss of a medical record is very different to losing a credit card. If your credit card is stolen, your bank can make you financially whole again, and give you a new credit card. A month later, the implications are minimal, and your credit history is clear. But if someone gets hold of information about your medical history, that knowledge cannot be cancelled and replaced – you can’t change the dates of birth of your children, and denial of a medical event can have serious health implications.

The Department of Health is correct that the identifier used to link all of an individual patient’s data together – the pseudonym, which you could equate to a credit card number – is effectively “unbreakable”, in the sense that it won’t reveal the NHS number from which it is derived. No one credible has ever argued otherwise. You cannot readily identify someone from their credit card number.

But that misses the point that there are plenty of ways to identify an individual other than their NHS number. This is not a new point, but it has never been addressed by NHS Digital or the Department of Health. In fact, they repeatedly ignore it. It was medConfidential that redacted the dates from the graphic above, not the company who published it on their website.

Whenever we talk to NHS Digital or the Department of Health, they repeatedly argue their use of pseudonyms as linking identifiers keeps medical information safe because they hide one of the most obvious ways to identify someone, i.e. their NHS number. We don’t disagree, and we agree that making the pseudonym as unbreakable as possible is a good idea. But what this utterly fails to address is that it is the very use of linking identifiers that makes it possible to retrieve a person’s entire hospital history from a single event that can be identified.

Focussing narrowly on the risk that the linking identifier could be “cracked” to reveal someone’s NHS number misses the far more serious risk that if any one of the events using that pseudonym is identified, the pseudonym itself is the key to reading all the other events – precisely as it is designed to be. That multiple events are linked by the same pseudonym introduces the risk that someone could be identified by patterns of events as well as details of one single event.

In the same way that you cannot guess someone’s identity from their phone number alone, you won’t be able to guess someone’s identity from their linking identifier. But just as in reading your partner’s phone bill, you could probably figure out who some of the numbers are from knowledge of the person, such as call patterns and timings. And once you’ve identified someone’s number, you can then look at other calls that were made…

Hospital Episodes Statistics (HES) provides all that sort of information – and allows the same inferences – for the medical history of any patient who has been treated in an NHS hospital, about whom you know some information. Information that may be readily accessible online, from public records or things people broadcast themselves on social media.

In the event of an accident that leads to HES being ‘published’, this is what NHS Digital says “could happen” – allowing people who know, or decide to find out something about you, to identify your medical history. This is how, in the event that one thing goes wrong, the dominoes destroy your medical privacy and (not coincidentally) the medical privacy of those directly connected with you.

Returning to the example of the phone bill – from a call history, you could infer your partner is having an affair, without knowing any details beyond what’s itemised on the phone bill.

Linking identifiers are necessary to make medical information useful for all sorts of purposes but, for reasons that should now be obvious, they cannot be made safe. That is why safe settings and opt outs are vital to delivering usable data with public confidence.

With 1.5 billion events to search through, what does this mean in practice?

Health events, or accidents, can happen to anyone, and the risk of most people being individually targeted by someone unknown is generally low – a risk the majority may be prepared to take for the benefit of science, given safeguards. But while it may be fair to ask people to make this tradeoff, it is neither fair nor safe to require them to make it.

As an exercise, look in your local newspaper (or the news section of the website that used to be your local newspaper) and see what stories involve a person being treated in hospital. What details are given for them? Why were they there? Have you, or has anyone you know, been in a similar situation?

The annex to the Partridge Review gives one good example, but here are several others:

- Every seven minutes, someone has a heart attack. This is 205 heart attacks per day, spread across 235 A&E departments. If you know the date of someone’s heart attack (not something normally kept secret), the hospital they went to, and maybe something else about them, using the Hospital Episode Statistics, their entire history would be identifiable just out of sheer averages.

- If a woman has three children, that is 3 identifiable dates on which some medical events occurred (most likely) in a hospital. Running the numbers on births per day, 3 dates will give you a unique identifier for the person you know. Are your children’s birthdays secret?

- If misfortune befalls someone, and information ends up in the public domain due to an incident that affects their health, (e.g. a serious traffic accident), or a person who is in the public eye, or with a public profile who publicly thanks the NHS for recent care (twitter), how many events of that kind happen to that kind of person per day? The numbers are low, and the risk is very high.

More information simply makes things more certain, and you can exclude coincidences based on other information – heart attacks aren’t evenly distributed round the country, for example, and each event contains other information. Even if you don’t know which of several heart attack patients was the person you know, it’s likely that you have some other information about their person, their location, their medical history, or other events that can be used to exclude the false matches.

It only takes one incident to unlock your entire hospital history. All that protects those incidents is a contract with the recipients of HES to say they will not screw up, and the existence of that contract is accepted by the Information Commissioner’s Office as being compliant with its “anonymisation code of practice”, because the data is defined as being “anonymous in context”.

This may or may not be true, but relying on hundreds of companies never to screw up is unwise – we know they do.

All this goes to explain why the Secretary of State promised that those who are not reassured could opt out: