The existing ‘Atos’ process* for Employment and Support Allowance (ESA), some components of Universal Credit (UC) and Personal Independence Payments (PIP) is recognised to be brutal and inhumane. The Department of Work and Pensions’ desire to replace it is fundamentally to be welcomed.

Where DWP ends up with regard to health information will likely be something modelled on the British Medical Association’s agreement with the Association of British Insurers on GP reports. This agreement provides a published definition of what data is medically relevant, with clear standards and a template form in which a report must be produced, including the structures and uses to which the data can and cannot be put, and a commitment on the part of the data recipient (in this case, the insurance company) to respect the medical view.

It is this last element with which DWP is most likely to struggle – but without it, all the rest is undermined.

The information a patient gives to their doctor(s) must be untainted by external priorities, otherwise people will come to harm – whether from excess or under-reporting. As Professor Helen Stokes-Lampard, chair of the Royal College of GPs has said, “We are doctors, whose first interest is the care of our patient: we are not border guards, and we are not benefits assessors.”

Were data sharing with DWP to be perceived in this way, the provision of care and medical research – and public confidence and trust in both – would be undermined to a far greater extent than care.data ever did.

Such data sharing would arguably be more dangerous and harmful overall than the Atos assessment process, as GPs would have consider competing incentives around the information provided by their patients – not knowing in advance which Departments would get to see it, nor when DWP might send letters demanding they change their medical judgment.

DWP cannot address these issues alone and in secret – a tender is never a good place to start, and the current one could potentially catastrophically undermine any improvements.

There aren’t many ‘fully automated’ decisions

Were a third party being contracted to make automated decisions, DWP could (and should) expose the ‘business logic’ upon which those decisions are to be made. But that is not what DWP is doing.

Some of the decisions being made are really, really simple – being pregnant, for example, is a binary state indicated by a medical test, from which processes can result. And a ‘terminal’ state is a medical decision, made for medical reasons.

While the actions of DWP and its contractors may suggest that some terminally-ill patients are ‘fit for work’, we do not imagine this to be an explicit policy intent – more a result of the systematic process neglect that the current Secretary of State has expressed a desire to resolve. Will DWP accept a ‘terminal’ definition from the NHS in future? If not, as now, nothing that DWP does will matter.

Most areas of controversy are not fully automated, nor even fully automatable. While a recorded status of ‘terminal’ may (trivially) be the result of a human pressing a button, when the doctor presses that button has to be based on a carefully considered discussion with the patient – which should only be about how they wish to die, without any implications or insinuations from target-obsessed bureaucracies of the state.

Medical decisions are human decisions

The Atos processes exist because DWP does not trust the data it could get from the NHS. As has become evident, there are processes where NHS doctors offer ‘fit notes’ the DWP requires them to provide, but pressures them not to. This is DWP gaming the very system that it set up in an attempt to make it not be gameable by anyone else. And this remains the context in which the tender has been issued.

Patients must believe that the information they give to their doctor will not be used against them. No data protection law, old or new, allows the DWP to rifle through GP records without an explicit legal case. However the Atos process is replaced, whatever replaces it is going to require new legislation – informed by all of the stakeholders, in a public debate.

DWP brings ‘business logic’ to a political problem

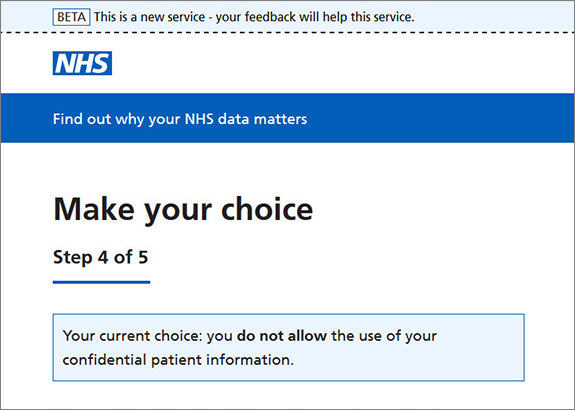

Any data access or data sharing cannot be done under Data Protection law alone. It is not part of the NHS’ or GP’s public task to assess benefits for DWP, and DWP cannot ‘ask’ for consent when that ‘consent’ is a condition of the social safety net that makes it possible for a person to buy food. (DWP may try; it will fail.) So any replacement is going to require primary legislation – and that legislation cannot be initiated by DWP alone, and certainly not by issuing a tender.

The tender document is quite clear on the policy intent, and how DWP sees the world. But DWP cannot fix this alone. It may try because it believes it has no other levers to pull, given wider distractions. So this current approach – trying to fix a complex political issue with more technology – will likely go no better than the Home Office’s roll out of the Settled Status digital process, and could go a lot worse…

Technical barriers imposed by others

DWP has no way of knowing that some of these barriers even exist.

For example, the new ‘NHS Login’ service will be necessary for any digital service that interacts with the NHS. And, in an explicit decision decision by NHS Digital (we argued against it; they ignored us, in writing), the NHS Login service passes the patient’s NHS number to every digital service.

While this may be good for direct care, it is terrible for anything else. As a result, any DWP ‘data broker’ or ‘trusted third party’ using the NHS Login will have a copy of the patients’ NHS number that the NHS would argue they are prohibited by law from having.

On an even more fundamental matter, the DWP is going to have to work with the NHS and medical professional bodies if only for the reason that it has little – if any – experience with coded health data on which the health service runs. Interpreting a person’s condition into (or from) dated medical events is a highly-valued clinical skill and, on the evidence of the outsourced work capability assessors, not one that will prove easy to duplicate.

We also have a further, modest, proposal.

* By ‘ATOS process’, we mean the Work Capability Assessment for ESA or UC – run by Centre for Health and Disability Assessments Ltd, a subsidiary firm of Maximus – and the assessments for PIP – run by Capita and an arm of Atos, trading as ‘Independent Assessment Services’.